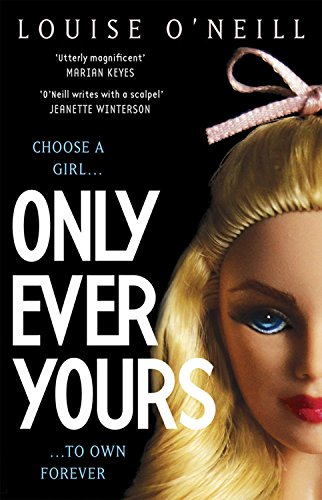

Young Adult fiction is feeling particularly exciting at the moment. Whether authors are talking mental health, friendship, gender identity, or just how excruciating adolescence can be, the buzz around books for teens is growing ever louder. Being at the tail end of my teens, I must admit I don’t pick up that many YA novels these days (blame my degree, which errs more towards Paradise Lost than contemporary fiction). But I made an exception for Louise O’Neill’s Only Ever Yours, recently shortlisted for the first ever YA Book Prize. I kind of had to. It’s all about body image and beauty and bitchy social circles – aptly described by lots of people as having elements of both Mean Girls and Margaret Atwood. It was inevitably going to tick a lot of boxes for me.

The novel imagines a dystopian society where ‘Eves’ are bred and brought up with one aim: male gratification. Their only goal is marriage. Preparation revolves around appearance and passivity. These young women (and they are so very young) must be continually gorgeous, slender, well groomed - and always in fierce competition with one another.

O’Neill writes with an attuned, often brutal, sharpness. The book is populated with girls who are addicted to Myface, constantly posting images online for others to admire. They are judged wholly on their ability to take up as little space as possible, reducing and reducing their bodies down to bone. All they know is a future as a decorative object. They are shaped to fulfil every whim of the man who will eventually claim them.

I spoke to O’Neill about her book, as I knew her time working in the fashion industry had heavily influenced her writing:

“Rereading Only Ever Yours, I can see how a myriad of my personal experiences shaped the narrative; from my education at an all-girls convent school, to my battle with anorexia and bulimia.”

Her exposure to the world of magazines and beauty products and clothes samples played a huge part in her perceptions of appearance too:

“It was only when I started to write my book and to consciously reflect upon my experience of the industry itself that I began to understand how problematic this really is. While I think fashion is an art form, and a vital tool for many women and men to express themselves with, there are many issues in the industry that need to be addressed. The fetishisation of extreme thinness, the obsession with young, prepubescent girls, and the pervasive race problem that allows twelve years to pass before a black model is featured on the cover of British Vogue again.”

All of these problems are nodded to in Only Ever Yours, sometimes subtly, sometimes with startling emphasis. O’Neill has constructed a world where everyone is measured and valued according to strict criteria: youth, body size, skin colour, and their ability to be attractive. Woe betide anyone like Freida (the protagonist) – simultaneously an outsider and a conformist desperate to be accepted – who is unable to play the game.

It’s not just a satire on the fashion industry though, but commentary on something more pervasive:

“The sheer volume of information that we are exposed to now, via magazines, TV, the internet, Instagram etc ensures that we are constantly kept in a state of wanting - I want that top, I want that lipstick, I want those legs, I want to have that face - and in that state of wanting, we are perfect consumers. We will buy and buy and buy, anything to try and fill up that gnawing sense of emptiness within us. We believe the fallacy that if we look a certain way that we will, finally, be happy.”

Does she think there’s any potential for change, for the fashion industry (and our society in general) to be celebratory, rather than encouraging us to see our figures and faces as some sort of failure?

“If young girls were to see a range of female bodies in magazines, from tall to short, fat to thin, white to black, and every other shade in between, they might not feel the same pressure to conform to a homogenised idea of beauty.”

The entire narrative of Only Ever Yours takes place in a school where the walls, the tables, and every other available surface are mirrored. They throw back images of these young women; reminding them that they’re never enough, always open to improvement. In many ways, this novel is a mirror too. In that grim future world, we see a distinct, grotesquely distorted reflection of the way things currently are. Hopefully books like this can galvanise change though – asking us to face those uglier aspects of our culture, and challenge them, change them, call bullshit on the corrosive message that you are only ever the sum of your looks. These characters have no choice. We do. It’s time to shout a little louder.

***

Words: Rosalind Jana

Rosalind Jana is reading English Literature at Oxford. She won the Vogue Talent Contest in 2011 at the age of 16, with a satirical take on an agricultural show written in ‘fashion show’ style. Visit Rosalind’s blog: Clothes, Cameras & Coffee